Text Film

Unlike most of the topics discussed in this section, ‘text film’ is not a recognised term denoting a specific practice; rather it describes a broad tendency in independent and experimental cinema in which written texts are introduced into the visual fabric of the film. Scott MacDonald, in one of the few books on the subject, opts for the more general term ‘screen writings’, describing a genre of works in which filmmakers merge the textual and the pictorial, bringing about a kind of cinematic literature.

Historically, written text in film, and consequently the act of reading, has been relegated to inter-titles describing the narrative action, and then later to subtitles in foreign-language films. This subservience to narrative and visual content has been challenged from as early as the 1920s, in avant-garde films such as Marcel Duchamp’s Anemic Cinéma (1926) and Man Ray’s L'Etoile de mer (1928) and Les Mystères de Château de Dé (1929), as well as Fernand Leger’s Ballet mécanique (1926). These films explore the creative possibilities of text on the screen, either in a dialogue with, or as a substitute for, the images themselves. The 1921 film Manhatta (Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand) is one of the earliest examples of poetic texts and images working together in equal measure.

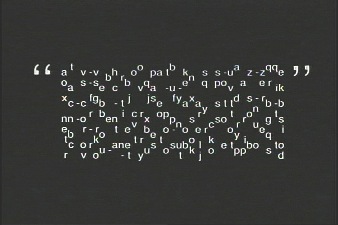

Later, in the 1950s and ‘60s, filmmakers associated with the Lettrist and Situationist movements scratched written messages directly into the filmstrip as a way of ‘speaking’ through the film material, but also of directly violating the material and thus the ideology of conventional image-making. The 1970s and ‘80s saw the most sustained use of text as image in experimental film, partly as a way to explore language and communication following the explosion of interest in Structuralism and semiotics. So Is This (1982) by Michael Snow consists entirely of words presented on the screen which the viewer reads in a successive manner, and Peter Rose’s Secondary Currents (1982) displays a series of inter-titles whose meaning eventually dissolves into something resembling both concrete and digital poetry.

The recent work of the Internet artists Young Hae Chang Heavy Industries strengthens this overlap, demonstrating the extent to which digital technologies blur the boundaries between the arts.

These explorations into words on the screen combine two, traditionally separate, modes of reception: viewing (images) and reading (text). What happens in the processing of these hybrid works? To what extent does context or artistic medium affect the way we read?

Further reading

Scott MacDonald, Screen Writings: Scripts and Texts by Independent Filmmakers. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Jessica Pressman, ‘The Strategy of Digital Modernism: Young Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s DAKOTA, MFS Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 54, number 2 (Summer 2008): 302-326.

P. Adams Sitney, ‘Image and Title in Avant-Garde Cinema’, October, Volume 11, Essays in Honor of Jay Leyda (Winter 1979): 97-112.

Bart Testa, ‘Screen Words: Early Film and Avant-Garde Film in the House of the Word’

William Wees and Michael Dorland (eds.), Words and Moving Images. Montreal: Médiatexte Publications, 1984.